Sally Bick’s excellent volume Unsettled Scores shines a bright light on the enormous and influential contribution that Hanns Eisler and Aaron Copland’s first Hollywood film scores played in breaking the film music mould and serving up modernist classical music to cinema goers.

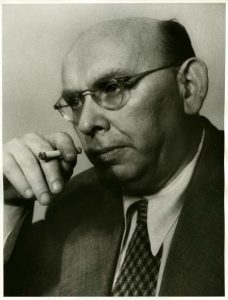

Hanns Eisler – often referred to as the “Karl Marx of Music”. He deserves far more recognition for the way that his scoring techniques laid the foundation for modern film music.

Prior to reading Unsettled Scores by Sally Bick I must confess that as much as I knew about Aaron Copland the opposite was true for Hanns Eisler. For sure, I would have come across his name whilst reading accounts of the lives of Copland and Leonard Bernstein and I was aware of the Woody Guthrie song Eisler on the Go sung by Billy Bragg and Wilco. I knew the name but couldn’t place it in the pantheon of film composer greats. However, thanks to this well researched and engagingly written book that has now changed.

Bick argues that the techniques they developed on their first forays to Hollywood shifted the industry’s paradigm. The use of well-placed dissonance, drawn out stinger chords, passages of twelve tone music and use of silence to increase the on screen tension were revolutionary and paved the way for modern film composition technique for horror and psychological drama. Prior to Copland and Eisler most film music was either overblown, lushly orchestrated and bore no relation to the narrative or at the other extreme was too obvious, indiscriminately exploiting the Leitmotif technique or musical rendering of the action on the screen – so called Mickey Mousing. Bick describes in detail how Copland and Eisler developed ways to communicate ideas not conveyed in the storyline, the unspoken thoughts of the protagonists or develop audience understanding of the symbolic goals of a film.

There are lots of parallels between Copland and Eisler. Both were at the cutting edge of modernism – Copland was taught by Nadia Boulanger and Eisler by Arnold Schonberg. Both were not from wealthy backgrounds so Hollywood presented an excellent opportunity to make money. Both wrote extensively about film music and were highly critical of contemporary practices. Both had relatively short Hollywood careers – Copland scored five movies from 1939-48 and Eisler eight movies from 1943-1947. Both wrote music for controversial war time films and this combined with their left leaning (in Eisler’s case Marxist) politics meant they were obvious targets for the House of Un-American Committee (HUAC).

The book is divided into five chapters. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to the two main characters, and the state of Hollywood film music in the late 1930s. Chapters 2 and 4 deal with Copland and Eisler’s extensive writings on film music and Chapters 3 and 5 deal with their first experience of working in Hollywood and provide examples of what made their scores so special.

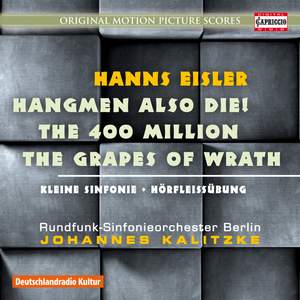

Both Copland and Eisler worked on prestige pictures: Copland provided the score for the Lewis Milestone adaptation of the John Steinbeck novella Of Mice and Men (1939) whilst Eisler was drafted in by his German émigré colleagues Fritz Lang (Director) and Berthold Brecht (Writer) to compose music for Hangmen Also Die (1943). Both films were attractive to the composers based on their political beliefs and provided them with the opportunity to express these to a wider audience. Of Mice and Men deals with the fate of migrant workers George and Lennie who have an unrealizable American dream to own their own ranch, tend rabbits and live off the fat of the land. Hangmen Also Die is based on the true events involving the assassination of Reinard Heydrich the Nazi Reichsprotektor of Czechoslovakia and the subsequent investigation and terrible recriminations for the Prague citizens.

Both Copland and Eisler worked on prestige pictures: Copland provided the score for the Lewis Milestone adaptation of the John Steinbeck novella Of Mice and Men (1939) whilst Eisler was drafted in by his German émigré colleagues Fritz Lang (Director) and Berthold Brecht (Writer) to compose music for Hangmen Also Die (1943). Both films were attractive to the composers based on their political beliefs and provided them with the opportunity to express these to a wider audience. Of Mice and Men deals with the fate of migrant workers George and Lennie who have an unrealizable American dream to own their own ranch, tend rabbits and live off the fat of the land. Hangmen Also Die is based on the true events involving the assassination of Reinard Heydrich the Nazi Reichsprotektor of Czechoslovakia and the subsequent investigation and terrible recriminations for the Prague citizens.

George and Lennie in the final scene of Of Mice and Men.

Following Copland’s largely positive experience on the set of Of Mice and Men, Copland put together a 58 page lecture for the Museum of Modern Art. Much of the theory (including his 5 tenets see box) was later modified and updated in his books Our Music and What to Listen for in Music. Whereas Copland’s publishing exploits were straightforward, Eisler’s were anything but. In fact, Bick delves into this in such detail that the authorship of Composing for the Films is very much like an old fashioned Who Done It! Between 1938-40 Eisler worked at the NY New School for Social Research, a job that involved commenting on film scores and composition (of new scores and alternative versions of existing ones). This post led to a commission to write a book on the subject. However, this quickly became a poison chalice. Trying to write a book in a foreign language whilst holding down an academic job and also latterly composing for Hollywood was too much and the publication date crept ever further away. The under pressure Eisler recruited a colleague called Ernesto Adorno to help him but this only added to the difficulties as Adorno and Eisler were not natural collaborators. Adorno spoke the better English and was responsible for the translation from the original German but he withdrew his name from the publication when it became obvious that the books highly politicised views on Hollywood and the capitalist nature of American film making would bring unwanted attention from Joe McCarthy and HUAC. The book was largely dismissed at the time of its publication in 1947 as Marxist dogma and it was almost certainly responsible for Eisler’s deportation order in 1948. In more recent times it has become extremely influential text. However, the controversy of who was the main author has never been resolved with numerous versions released down the decades either solely in the name of Eisler or Adorno or as Adorno & Eisler. Although this section was intriguing it did come across a little repetitive and more akin to an academic paper.

| Bick shows that in their writings Copland and Eisler often came to very similar conclusions: Copland’s 5 tenets suggested that film music should: • Help create a more convincing atmosphere of time and place • Underpin psychological refinement and allow the audience to understand the unspoken thoughts of a character or the unseen implications of a situation • Sometimes function as a neutral background filler - such subordinated music can be highly manipulative as it functions subconsciously • Build a sense of continuity by bridging disparate scenes • Underpin the theatrical build up of a scene and rounding it off with a sense of finality Eisler and Adorno proposed a number of principles that they believed would improve Hollywood scoring for instance • The use of shock as opposed to the banality of Hollywood – they felt that often the titles were like an advert and too triumphant and uplifting • They advocated musical techniques that reflected a higher truth and challenged manipulation encouraging the audience to come up with their own view rather than being told what to think • The use of counterpoint was viewed as crucial to communicate an idea or political view not conveyed on the screen • They argued that for more modernist styles being used in film saying that even the unaccumstomed ear can find complex musical devices more understandable when accompanied by visual images. |

|---|

Bick does make it clear that Eisler and Adorno sought limited engagement with other works or authors in the production of their book. Also, as they don’t refer to the works of art composers (like Copland, Antheil or Thompson) and their Hollywood compositions one is left wondering if Eisler appreciated their film work or even was aware of it. There’s not much discourse to suggest there was much contact between Copland and Eisler apart from the fundraising that Copland was involved in to help Eisler’s defence against the HUAC investigation. I was left wondering if they had anything more than a mild acquaintance and held much mutual respect for eachother’s works. Considering Bick’s 60 pages of sources I guess if there was any evidence of this she would have found it!

Bick on occasions sticks to her remit somewhat too rigidly for my liking. As a result some stones are left unturned and interesting nuances overlooked. For instance much is made of the unprecedented freedom and privileged working conditions Copland experienced whilst working on Of Mice and Men. The luck of working with and independent producer afforded him more time to compose the score, closer collaboration with the director and more control over the final edit of music to picture. The obvious counterpoint to this was Copland’s much less satisfactory final Hollywood experience with The Heiress (1949) directed by Samuel Goldwyn. A perfectly amicable relationship was ruined on the whim of Goldwyn who at the last minute ripped out the guts of Copland’s prelude and replaced it with a saccharine and schmaltzy version of the song Plaisir d’Amour by studio composer Nathan van Cleave. Copland publically disowned this part of the score. Ironically he won an Oscar but his outburst combined with the taint of the Red Scare (and possibly his increased price tag) meant that he never worked in Hollywood again. You can read more about this episode in this excellent blog (and my review of Paula Musegades Aaron Copland’s Hollywood Film Scores).

In addition, it would have been interesting to get the author’s opinions on how Copland and Eisler dealt with a similar brief. For instance both scored documentaries exhibited at the 1939 New York World’s Fair but this is not explored. Also, in the same year that Eisler was composing for Hangmen Also Die, Copland was working on another “How Hollywood should fight the war” movie The North Star (1943) which dealt with an uprising of a village in Ukraine against Nazi occupiers carrying out similar atrocities to those in Hangmen Also Die. As Copland’s involvement in this pro Soviet film was one of the main reasons that he ended up in front of HUAC this really should have been mentioned. Another tantalising comparison would have been that between Copland’s score for Of Mice and Men and Eisler’s alternative score that he penned for The Grapes of Wrath (the original was by Alfred Newman) whilst in his teaching post. Considering both stories were by Steinbeck and involved migrant workers and dispossessed farmers it would have been revealing to get Bick’s views on how they dealt with such similar materials based on their quite different political ideologies.

The chapters of Unsettled Scores dealing with the scores and musical examples are highly informative. The discussion about the Death of Candy’s Dog cue is particularly enlightening and brings Copland’s genius for using simple scoring and lean instrumentation into sharp focus. His use of a descending two note viola motive followed by a single drawn out flute note is masterful, at once incredibly moving and suspenseful. There is definitely a feel of The Last Post being sounded before the poor dog is shot.

Considering both Copland and Eisler described the need for music to communicate the unspoken thoughts of a character or the unseen implications of a situation, it seems really odd that the music that accompanies the Mae at Home and the Mae in the Barn cues are not discussed. She’s the only female with a notable role in the story and is treated badly by everyone. In the entire film only once does a character contradict this convention (when Slim says “Poor Kid, I should have talked to her”) and even that is not to her face. However, Copland’s music makes it obvious that she like George, Lennie, Candy and Crooks is deserving of our sympathy for her situation, lonely on a ranch with no female company, anyone to talk to and a bullying, controlling husband in Curley.

Perhaps this omission from the text has something to do with the relative lack of music to deal with in Eisler’s score for Hangmen Also Die. On watching the film I was surprised just how sparsely music is used. There’s around 6 minutes of original music compared to around 40 minutes in Of Mice and Men. Although, there is repetition of Copland’s themes, this disjuncture probably was an issue for the author. If all the cues in Of Mice and Men were discussed then the book may have come across as too much discussion on Copland’s score and not enough on Eisler’s. It’s surprising that the author doesn’t remark on this as for the casual observer it is such a marked contrast. The lack of music in Hangmen Also Die heightens the tension whilst the use of music in Of Mice and Men seems to carry the narrative to the inevitable sad ending.

Although Eisler’s score was brief Bick uncovers a wealth of fascinating information. It appears that the director Fritz Lang wished to water down some of Brecht’s more political machinations of the story and so it was down to Eisler to get some of these more leftish views across through his music. For instance, he considered modernist music to be the enemy of Fascism so his use of twelve tone music in the titles is significant as it symbolises the struggle of the Czech underground resistance. The author also points out the inclusion of several in jokes, irony and covert ideals meant to outsmart Lang and the censors. As such Eisler comes across as an inverse Dmitri Shostakovich who contemporaneously behind the Iron Curtain was frequently trying to camouflage his true musical personality amidst works that fulfilled the Communist Party line.

One of the Czech hostages gives the No Surrender victory sign before being taken off to be executed by the Nazis. (Note: The V sign has a very different meaning in the UK!)

Whilst dealing with hidden meaning, I was amazed to find out that after being deported from the US that Eisler ended up using a short piece from the cue when the Czech underground leader is on his death bed as the theme for the East German national anthem. Considering his views on Hollywood and his ignominious exit from the US this must have been his way of getting one back at the Americans in the form of his own No Surrender V sign.

There are a couple of editing glitches in the otherwise superbly produced book. The first is rather minor but it is a shame that all the musical cues for Hangmen Also Die are not listed at the end of the Eisler section to mirror that at the end of the Copland section.

A much more important flaw involves the references to musical cues. The University of Illinois Press has created a very welcome accompanying website where all the musical cues can be located and watched on YouTube. These are denoted in the text with text such as 5.2.1. The explanation directing readers to this important resource should be on the frontispiece of the book but instead is buried deep within the notes section (Note 67 of Chapter 3 on pg. 177). I hope that the publisher will find a way of rectifying this in existing books (e.g. adding a sticker with the link) or making it clearer if there is a reprint.

There are comparitively few examples of Eisler’s film music available on disc or streaming. It’s a pity!

Some of this critique may seem a bit picky but I would like to counter this interpretation. In fact it is because I enjoyed the book so much and found it to be so informative and thought provoking that I have been inspired to wonder about these avenues not explored. Like me I am sure that very few people recognise the enormous contribution that Hanns Eisler made to Hollywood scoring techniques but I am also sure that people who read this book will be very keen to explore his music. Furthermore, I hope that record labels are will be more inclined to release more of Eisler’s cinematic works in the future. Over the last couple of decades this part of Copland’s lexicon has been more widely available and for me represent the most important Copland releases in that time.

One final point – Unsettled Scores has many superb quotations throughout. In her conclusion, Bick cites Peter Burkholder who said that in comparison to 20th century art music, the music of no other period has been “so hated, so ignored, so little played or understood”. She adds “Yet ironically musical modernism has found a very secure place in the genre of film thanks in part to Eisler’s and Copland’s efforts”. It sums it up brilliantly.

Book details:

- Publisher: University of Illinois Press (16 Dec. 2019)

- Series: Music in American Life

- Paperback: 240 pages

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 0252042816

- ISBN-13: 978-0252042812

Blog Comments

Sally Bick

28th August 2023 at 9:17 pm

Dear Kevin, if I may,

Many thanks for your thoughtful review of my book, which I appreciate. Your blog and website, by the way, is really terrific–a wonderful resource for readers and “listeners.” Many thanks for the work you do for those interested in Copland.