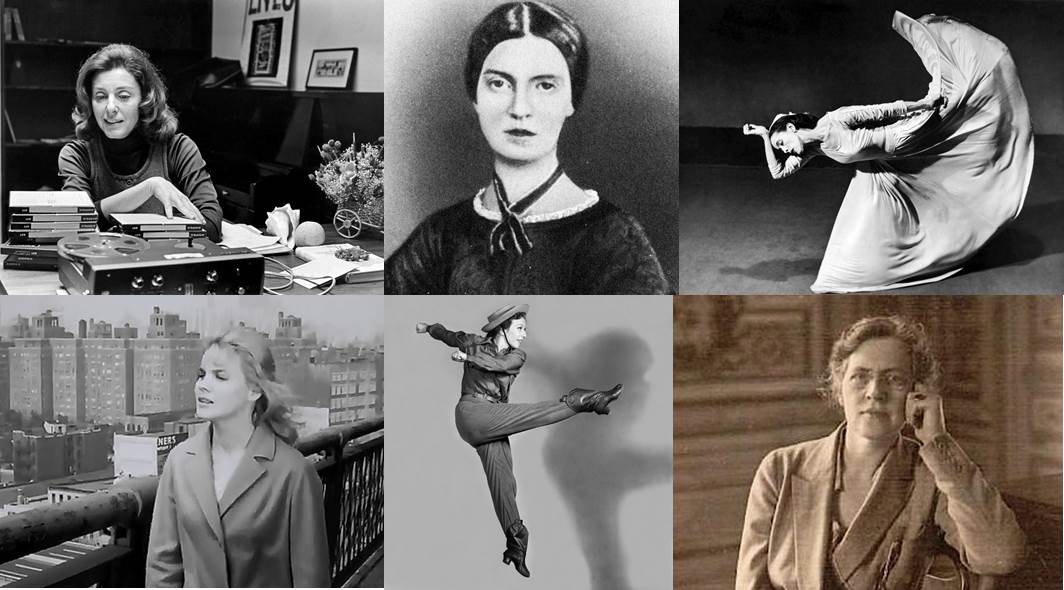

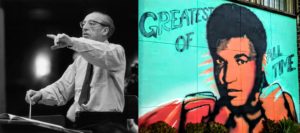

Throughout Aaron Copland’s life there were very important women who played a major role in inspiring his creativity towards producing his unique sound and some of his most iconic works. His career choices and success often hinged around suggestions from, mentoring by and commissions from women. Furthermore, he frequently was drawn to works by women poets and stories with interesting, strong, complex female central characters. On International Women’s Day this blog is a celebration of the females both real and imagined that supported and inspired Copland throughout a lifetime in music.

Right from the word go Aaron Copland’s course to a musical career was set by his mother Sarah who paid for music lessons and his sister Laurine who helped teach Aaron to play the piano. The latter was also a cheerleader in persuading his parents to send Copland to study in Paris and later encouraging him to take up conducting. It’s impossible to listen to the piece Letter from Home without hearing the love and affection for his family. The work was written in 1944 when Copland was in Mexico and received a series of letters from his sister telling him about his Mother’s heart attack and later death.

When he got to Paris in June 1921, Copland found himself sat at meal times next to the harpist Djina Ostrowska. It was through Ostrowska that Copland first learnt about Nadia Boulanger at the Fountainbleu School and she urged him to go along and listen to one of her harmony classes. It was lucky that Copland responded to Ostrowska’s persuasive enthusiasm as this would prove to be a pivotal moment in both his and Boulanger’s musical life.

Aaron Copland on bicycle, with harpist Djina Ostrowska, Fountainebleau.

Photograph retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/copland.phot0093/ Used by permission of The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc., 254 West 31st Street, 15th floor, New York, NY 10001, (212) 461-6956, fax: (212) 810-4567.

Her sense of involvement in the whole subject of harmony made it more lively than I ever thought it could be. She created a kind of excitement about the subject, how it was after all, the fundamental basis of our music, when one really thought about. I suspected that first day that I had found my composition teacher.

Boulanger was exactly the sort of teacher Copland wanted and needed – someone who knew all the latest trends and the main protagonists (Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Berg, Les Six and Jazz), who was a stern task master but also someone who immediately realised Copland’s talent and never wavered in her belief in her star pupil. They had a wonderful symbiotic relationship and fired each other’s interests. She pushed him to writing the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra and she played the organ at its premiere in New York. Other works written whilst at the Boulangerie with “Mademoiselle” include the ballet Grohg, Passacaglia for piano, the choral work Four Motets and the chamber art song for soprano, flute and clarinet As it fell upon a day.

Theirs was a lifelong friendship, full of affection and mutual admiration. Copland dedicated more works to Boulanger than any other person. In addition to the Organ symphony and Passacaglia he also dedicated to his former mentor the song Dirge in woods (1954) to mark Boulanger’s 50th year of teaching and the chamber work Nonet for strings (1960).

Of course one of the great benefits to Boulanger of this association with Copland was that he was right at the vanguard of a whole swathe of American and non-American composers that followed his example. Prior to this no famous composers learnt their craft from a woman but following fast on the boot heals of Copland she would go on to help hone the talents of such musical luminaries as Roy Harris, Virgil Thompson, Astor Piazzola, Quincy Jones, Philip Glass, Daniel Barenboim and many more.

Back in the States in the mid-1920s two pioneering women assisted Copland getting a foothold on the artistic ladder. Claire Raphael Reis and Minna Lederman were both involved in the establishment of the League of Composers. The former was Director from 1923-1948 whilst the latter was editor of the League’s journal Modern Music from 1924-1946. Reis arranged Copland’s first performance in New York and presented Copland with the League’s first commission which resulted in the classical jazz piece Music for the Theatre. This was such an important break for Copland that when he received the Pulitzer Prize for Appalachian Spring in 1945 he explicitly thanked her for setting him on course.

After all, you are an intimate part of my career, so you get the credit too!

Lederman who Copland nicknamed Mink, for her part published Copland’s first articles which opened up many opportunities for him to lecture and become a prolific author of numerous publications in the decades to come.

A series of other influential women helped finance Copland projects included Alma Morganthau Wertheim (provided a $1000 bursary in the late 20s), Mary Senior Churchill (supported the Copland-Sessions concerts) and Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge (commissioned Appalachian Spring and the Piano Quartet).

Two of Copland’s most famous works, the ballets Rodeo and Appalachian Spring involve stories with strong characterful women at the centre. In addition, both were choreographed by women, Agnes de Mille and Martha Graham who also danced the lead roles. In Rodeo the feisty cowgirl has to beat the cowboys at their own game before showing her femininity and winning the heart of the Champion Roper at the Saturday Night dance. Agnes de Mille said:

She acts like a boy, not to be a boy, but to be liked by the boys

Appalachian Spring involves two main women characters The Bride who is staunch and resilient and the Pioneer Woman who offers wisdom and sympathy.

Copland was always an avid reader of poetry and was particularly attracted to the poems of Emily Dickinson saying “they seemed very meaningful to me”. As often in his compositional career he was ahead of the game and set 12 Poems to music even before Thomas Johnson’s 1955 edition, the first complete and accurate collection of her work. Copland started with The Chariot. He said:

I thought, ‘My heavens!’ This little girl, or young woman, in this little town in Massachusetts, riding off into immortality with death himself, was such an extraordinarily magnificent picture. Not many people would even think of such a thing, no less an apparently modest woman leading such a modest life. And I began reading a lot about her. And then I found another poem I liked and started to set and then another and another. And after I got to number twelve I decided that was enough and so I stopped!

The first biographer of Emily Dickinson in 1930 was written by another poet Genevieve Taggard. Copland would have almost certainly read this work and been influenced by it. He in fact set one of Taggard’s poems called Lark for baritone voice & mixed chorus (SATB) in 1938 with the song of the lark representing the hope of President Roosevelt’s New Deal “Sprung like an arrow from the bow of dark”.

As with the aforementioned ballets, much of the programmatic work that Copland composed music for involved stories with heroines who were tragic, wronged or troubled. Be it with Mae in Of Mice and Men (lonely and bored and treated with suspicion and wariness by all the male characters), Catherine in The Heiress (unloved and gilted), Laurie in The Tender Land (idealistic and feeling different) and Mary Ann in Something Wild (victim of rape who tries to commit suicide) these complex characters must have intrigued Copland greatly as they really enabled him to compose incredibly poignant music from his top drawer.

Aaron Copland is known for promoting numerous contemporary composers in the various roles he held with the League of Composers and at Tanglewood and Yaddo. With regards the value of women composers, to some extent his views were very much of the time and he was puzzled by the fact that no past female composers could be considered great. However, he did opine that many modern female composers to be “writing music worth playing” and he programmed and promoted the work of several women including Ruth Crawford Seeger, Vivian Fine, Marcelle de Manziarly, Thea Musgrave and later Barbara Kolb.

In his mid-70s Copland’s thoughts turned to writing an autobiography. He met Vivian Perlis who was director of Yale University’s Oral History of American Music around the time of the Charles Ives centenary in 1974. They got on famously and when she finished the Ives project she turned her sites on recording Copland’s recollections. This led to the two volumes of autobiographies that they co-authored Copland: 1900 through 1942 and Copland: Since 1943.

The oft used phrase “Behind every great man is a great woman” is therefore only too true in the case of Aaron Copland. But rather than just one woman there were many truly pioneering women who helped make his life extraordinary.

May I also take this opportunity to thank the many wonderful, supportive, hard-working, intelligent and witty women in my own life.

Happy International Women’s Day!

The source material for this blog comes from the peerless books:

- Aaron Copland The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man by Howard Pollack. University of Illinois Press (2000) ISBN 0-252-06900-5

- Copland Connotations: Studies and Interviews Edited by Peter Dickinson. The Boydell Press (2002) ISBN 0-85115-902-8

Leave a Comment