I have been on a long journey (yes, another one!). In the beginning it wasn’t really a journey I wanted to take or was in any way prepared for. At times it felt like the path taken by Lewis and Clark across the Great Plains seeking to find a navigable route through the Rockies. It’s been tough and strenuous and tested me to the limits. There have been plenty of dead ends, quite a bit of going round in circles, lots of seemingly insurmountable objects or getting to one peak only to find another half dozen peaks ahead of me, and so often being faced with a vista that looked exactly the same as any other. There was no map or compass to help me – I was completely on my own. It’s been the biggest pioneering journey of my life but I have lived to tell the tail. I have been into the wilderness and come out the other side. And now I am ready to report on my findings and tell the world:

How I taught myself to love the music of Roy Harris!

Awakening

No book on Aaron Copland is complete without discourse on Roy Harris. Harris was perhaps more famous and successful than Copland during the 1930s. Oft described as the “Cowboy Composer” or the “Great White Hope of American Music”, today he is hardly known at all, even amongst seasoned concert goers. He has one tiny finger grip on the repertory with his Symphony No 3 – a piece often mentioned alongside Copland’s own Symphony No 3 when such works are discussed under the banner of the “Great American Symphony”.

For 25 years and more I have owned a few of Harris’s symphonic works. I listened to them once in a while, didn’t like them much and wondered why he was even considered in the same breath as Copland. It was a mystery to me and it bugged me. Why was he so famous then, and virtually unknown now beyond music scholars?

Lee J Cobb in Twelve Angry Men.

I have puzzled over this for years and every time I tried to gain an understanding I was put off right at the start. To me there was one phrase that came up in my head time and again as I listened to Harris’s music: “Grimly determined”. For me the music didn’t dance. It had no melody. It was boring and sounded all the same.

I was about to write something a year or so ago. A scathing account of his music as compared to Copland’s – highlighting all of its flaws. I was going to compare 10 works by both composers and give them a star rating. It was going to be a landslide victory for Copland. However, there was a danger of it being a kangaroo court, that I was going to convict Roy Harris without a fair hearing (or a fair listening!).

I was like Lee J Cobb from Twelve Angry Men. As far as I was concerned Harris was guilty:

It gets me how these lawyers talk and talk and talk. Even when it’s an open and shut case like this one. I mean, have you ever heard so much talk about nothing?

……Here’s what I think and I have no personal feelings about this, I just want to talk about facts.

……Now these are facts. You can’t refute facts. The kid is guilty!

As usual Copland (taking the role of Henry Fonda) spoke to me from the page and encouraged me to reconsider the evidence. He said:

I hold to the simple proposition that the only way to comprehend a “difficult” piece of abstract sculpture is to keep looking at it, and the only way to understand “difficult” modern music is to keep listening to it. (Not all of it is difficult listening by the way.)

If you hear this music and fail to realise that it has added a new dimension to Western musical art, that it has a power and tension and expressiveness typically twentieth-century in quality, that is has overcome the rhythmic inhibitions of the nineteenth century and added complexes of chordal progressions never before conceived, that it has invented subtle or brash combinations of hitherto unheard timbres, that it offers new structural principles that open up the vistas for the future – I say, if your pulse remains steady at the contemplation of all this and if listening to it does not add up to a fresh and different musical experience for you, then any defense of mine, or anybody else, can be of no use whatsoever.

“Are My Ears on Wrong?” A Polemic. From Copland on Music

(original article from the New York Times magazine 1955)

Copland was talking about modern classical music in general rather than Roy Harris in particular, but I was chided nevertheless. I realised that if I was to write such an account it felt imperative to be judicious and Copland like and give it as much attention as possible and be sure of my facts. And as always with research, when I started, I couldn’t stop looking, asking questions, turning up new leads, and travelling down lots of rabbit holes.

It’s been a lesson to anyone prone to knee jerk reactions.

Conflict

If you are embarking on a journey of discovery into a lesser-known composer, chances are you are going to start off from a positive standpoint. You might have heard a piece that you liked on the radio or in the concert hall or read a favourable review and are therefore eager to discover more. When I began this odyssey, I was starting from a very different place. My hypothesis was to prove why I didn’t like this music and why (unlike Copland’s) it had not endured.

Attempting to disprove this hypothesis is a challenge. A Harris piece will not find you unawares. You will have to go looking for it. This is because there is virtually zero chance of hearing Harris on the radio. Furthermore, as an unknown, forgotten, dead white bloke, with an ordinary, unflashy name he is also very unlikely to find himself on the programme of a concert venue near you. Roy Harris couldn’t be less Box Office. I’m afraid the Spotify algorithms are not going to be much help either and offer up a Roy Harris miniature for your delectation. Trust me, I listened to Harris solidly for a year and more and only then did Spotify realise that I might be choosing this music from my own free will. Up to this point virtually every time a Harris work, that I had picked came to an end, I was served up something light and airy by an English Pastoralist. It was as if the algorithms were issuing a declamatory commandment

Thou shalt not listen to Roy Harris!

So, the issue is that if you are willing to lend your ears to Harris, you are going to make that decision yourself and that means going in with your eyes open and no doubt your prejudices intact. If like me, you have struggled in the past to latch on to a rhythm or find a tune you will probably be thinking even before the first note “this is going to be a slog”.

I do feel sorry for Harris because there can’t be many other notable composers that would have to put up with such a pre-listen advisory warning!

Despite all this, and with Copland’s words of wisdom in my ear, I started challenging myself with some questions:

- If I did by chance hear this type of music playing on the radio, would it pique my interest?

- Would I want to know who it was composed by?

The answer to both questions was always an emphatic “Yes”.

Dedication

Roy Harris is hard to get to know.

If I like a piece of music or am intrigued by it, I need to know the context. I need to get under the skin of the composer and the times that they lived. However, this is difficult with Roy Harris as virtually every liner note essay is limited to the same tropes – born in a log cabin in Oklahoma on Lincoln’s birthday. That his family moved West when he was a kid, that before he became a composer, he drove a truck. That he made an indelible mark on American orchestral music. That he was largely self-taught, he used folk materials and wrote music that had an idiosyncratic, jagged, uncultivated sound. That he was a visionary and had a style all his own based on an autogenetic[1] approach. And that’s about it.

Most of the liner notes on a Harris CD will not go beyond this vague biographical sketch. Also, as Harris’s star had waned by the 1960s and 70s there are virtually no historical TV interviews on YouTube so it’s incredibly difficult to hear the composer in his own words. What you will get though are discussions on the music and lots of musical jargon terms. If you are a casual music lover, you are going to have to get used to a very particular vocabulary. It’s easy to get lost amongst the discussion on double and triple fugues, passacaglia, contrapuntal lines, poly tonal counterpoint, poly chordal harmony, divisi, polyphony, antiphonal textures etc etc. Whereas Copland looked to simplify his style to win a greater audience, Harris did the opposite. As his career progressed, his music became more complicated and required extensive explanation. It often makes for a tough read as well as a tough listen!

But listen and read I have. During this great adventure I have unearthed every Harris work available on Spotify and acquired around 15 albums on CD and vinyl and played every Roy Harris piece at least 10 times, the more notable ones (the Symphonies) around 20 times and some that were already in my CD collection (Symphonies No 3, Symphony 7 and 9) around 50 times.

I have read as much literature as I could lay my hands on. Unlike Copland there are very few biographies on Roy Harris. The few books that are available are hard to find and expensive. I have tracked them down, bought them, read each of them at least twice. Whether they liked it or not, I have kept my wife and parents fully abreast of my discoveries

in short, I have become a Roy Harris bore.

In my resolve to be exhaustive I have developed what some might suggest are obsessive and compulsive tendencies! No Harris work is much longer than 30 minutes. As a result, whenever I go on a long, solo car journey I tend to listen to each of his symphonies available on Spotify (1933, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9) one after another!

Gradually, ever so slowly I have made progress. Snatches of tunes have become ear worms. Where once all his music sounded exactly the same, I could pick out individual compositions and also recognise the bits which included recycled passages from other works (an activity that he did a lot). As with anyone who has conquered a fear or phobia or done something well, even though it was outside their normal comfort zone, I started to enjoy the endurance.

Affirmation

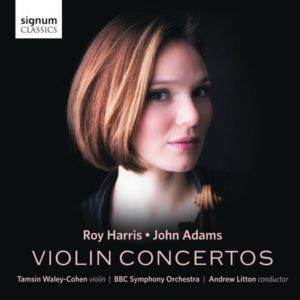

Two moments were pivotal in providing the chinks of light that I needed to begin the process of Roy Harris’s redemption. The first was when I saw and heard Harris’s Third Symphony played by the LSO at the Bristol Beacon. Such a hen’s teeth moment to see Harris performed live and in every sense brought to life. Then there was the discovery of Harris’s Violin Concerto performed by Tamsin Waley- Cohen, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Litton. It was a revelation and after only a couple of listens it started to sound like an American Lark Ascending. At last, I had found a Roy Harris piece that was truly lyrical and sang to me. I was amazed that this work had seemingly been lost and wondered why it wasn’t a mainstay in the orchestral violin repertory? Hearing it changed everything!

Two moments were pivotal in providing the chinks of light that I needed to begin the process of Roy Harris’s redemption. The first was when I saw and heard Harris’s Third Symphony played by the LSO at the Bristol Beacon. Such a hen’s teeth moment to see Harris performed live and in every sense brought to life. Then there was the discovery of Harris’s Violin Concerto performed by Tamsin Waley- Cohen, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Litton. It was a revelation and after only a couple of listens it started to sound like an American Lark Ascending. At last, I had found a Roy Harris piece that was truly lyrical and sang to me. I was amazed that this work had seemingly been lost and wondered why it wasn’t a mainstay in the orchestral violin repertory? Hearing it changed everything!

The four titles used in this blog: Awakening, Conflict, Dedication and Affirmation are the names of the four movements from Harris’s Symphony No 6: Gettysburg following Abraham Lincoln’s personal journey towards American Civil War victory and immortality. It seemed apt to use them in this blog. When I first listened to this work I thought it was decidedly below average. I actually wrote down in my notes that “Lincoln deserved better”. Like so many Harris works, by living with it for a time it grew on me and I started to appreciate its understated qualities.

All in all, my 18 month odyssey has felt like a musical pilgrimage – there was the initial doubt, the frequent setbacks, many times when it would be easier to turn back, and once in a while some hard won but notable revelations. But the arduous nature of the quest has made the final completion of the journey all the more rewarding. I am proud of myself – I have achieved something. I have changed my mind. Perhaps I’ll never be a Harris evangelist (like I am for Copland) but I am certainly a devout believer!

It’s also fitting that I feel that Copland is somehow encouraging me to be Roy Harris’s redeemer. Back in 1940, Copland in his book Our New Music wrote a chapter on Harris that could easily be interpreted as being a witness testimony for the prosecution. Although, Copland was relatively even handed and doled out plenty of plaudits, he certainly didn’t pull his punches on Harris’s shortcomings as a composer. I believe that the negative aspects of Copland’s treatise became the received wisdom and Harris never did manage to shake off this critical view.

Copland was prescient in imaging a musical future without Harris.

For whatever else we say about it, Harris’ music must be set down as vital in today’s American scene. It may have no lasting qualities whatsoever. No matter. It is still significant for us here and now, for it is on music such as this that future American composers will build.

Our New Music, 1940

By 1967 when Copland updated the book as The New Music, both composers were unpopular. In his tacked-on ending to the original essay Copland retreated from his earlier viewpoint and perhaps further cemented Harris’s long, slow descent into obscurity.

Also, my prognostication that the Californian composer was writing music on which “future American composers will build” now strikes me a downright naïve”…….Today’s gods live elsewhere.

The New Music 1900-1960

The revision concludes more positively but perhaps by then the damage was already done.

An English critic, not long ago, referred to Harris’ “inexhaustible fund of vitality”. It is this vitality, it seems to me, that will keep his music alive for future audiences of Americans.

The New Music 1900-1960

I know that despite his reservations that Copland rated Harris. I am also sure that he would be dismayed that his formal rival as America’s foremost composer was no longer played and rarely heard. I do feel duty bound to be his emissary, to try and right this wrong and bring the music of Roy Harris back from the brink of extinction!

Coming soon:

In future blogs I’ll be setting out my instruction manual on how you too can learn to like or even love the music of Roy Harris. I’ll also be covering the challenging relationship between Harris and Copland, that started as friends, turned to rivalry and later a high degree of enmity (from Harris to Copland at least). I’ll focus on Johana Harris, how she subjugated her career for Roy and her wonderful biography by Ethel Paquin which tells the incredible story of the “Mr and Mrs Music America”. I’ll also be sharing my theory on why Harris doesn’t get played these days – I don’t think it’s about the music which I now realise is worth it’s place.

If you want to know about Roy Harris – you came to the right place!

[1] Autogenetic means self-generated or originating from within. Many Roy Harris pieces start as a mere seed of an idea and seem to grow ever bigger from this tenuous beginning. His one movement symphonies No’s 3, 7 and 11 are good examples of this approach.

Leave a Comment