Last year on Mothering Sunday, as my son handed me my present, a CD, he said “I heard it on Radio 3. It’s just up your street. Somebody who does what you do – but she’s set it to music.”

The composer is an American, Julia Wolfe, who grew up in a small town in Pennsylvania called Montgomeryville. From childhood she remembers the dirt road and the surrounding fields which offered “an endless playground of natural forts and ice-skating rinks.” The road to the outside world led to Route 309, where a right turn takes the traveller to the city of Philadelphia and the left to ‘coal country’, the anthracite fields, where “everything in that direction seemed like the wild west.”

Wolfe previously composed ‘Steel Hammer’, a ballet based on the legend of John Henry who famously ‘died with a hammer in his hand’ and through this became more deeply involved in issues of American labour history, both local and national. When she was commissioned for her latest piece, she returned to her roots, and so far, so familiar, she went down coalmines, visited local museums where the lives of miners were depicted and commemorated. She interviewed old miners and the children of miners who had grown up in the ‘patch towns’, the U.S. term for a coal camp or ‘patch’ typically situated in a remote area where miners lived near the coal mine. She researched oral histories, traditional rhymes, newspaper reports and advertisements and included in her music an impassioned speech by John L. Lewis to the United Mine Workers Union. Finally, she made full use of the lengthy Mining Accident Index. I can see why my son detected a kindred spirit!

The result is “Anthracite Fields” – a choral symphony in five parts: Foundation, Breaker Boys, Speech, Flowers, Appliances.

For the Foundation movement, the singers chant the names of miners whose names appear on the accident index 1869-1916. Because the list is distressingly long, the composer chose to include only those whose first name was John and whose surname was of one syllable. The miners came largely from immigrant families, with surnames from Ace to Rudd, the more common Anglo-Saxon names familiar from any of our own local lists of miners, then for musical variation she included the exotic, those with longer surnames, German, Russian, Italian, from Santiarelli to Zamaconie by way of Ulrich and Svanevich. These conjour a fascinating cross section of a world of coalminers, all speaking in different tongues, whose workplace must surely have been likened to the Tower of Babel.

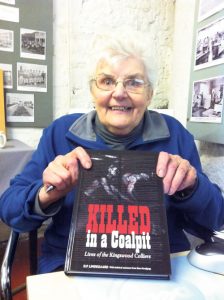

DP Lindegaard with her book “Killed in a Coal Pit – Lives of the Kingswood Colliers”

Readers of ‘Killed in a Coalpit’ my story of our own South Gloucestershire miners will find several among them who migrated to Pennsylvania in the mid-19th century, including one of my own ancestors. He suffered life-changing injuries in the mines there, though being called Jacob and having a surname longer than the regulation one syllable he would not been included in the chorale’s roll call of casualties. Jacob was only one member of several from my extended Pillinger clan who bravely took their families across the sea to the Pennsylvania mines ‘in search of a better life.’

The second section is called ‘The Breaker Boys’, with variations of the miners’ experience which quotes:

“I didn’t know how I got the nerve to go there in the first place. You didn’t dare say anything…..your fingernails, you had none, the ends of them bleeding every day from work, bleeding every day.”

The third movement uses a speech by John Llewelyn Lewis who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960 who fought for safe working conditions for these miners.

The penultimate part, ‘Flowers’ again tallies with the universal experience, “We all had flowers, we all had gardens. Flowers, flowers, flowers,” which echoes a phrase used by the Kingswood philanthropist, Henry Hill Budgett, who encouraged the provision of allotments for miners. He believed “a smiling garden” was essential to their well-being. Wolfe ends this part, “forget-me-not, forget me, forget me, forget-me-not.”

The U.S. anthracite fields supplied the power for everything from the railways to industry to domestic heating and the hundreds of appliances which people demanded and soon took for granted. But at a terrible cost: the lives of the miners. This is summed up in the Finale from an advertising jingle from 1900:

“Phoebe Snow about to go

On a trip to Buffalo

My gown stays white from morn to night

On the road to Anthracite”.

‘Anthracite Fields’ is not an ‘an easy listen’, and takes some getting used to, but for anyone – me – interested in the subject it is essential, and timely, especially now, when coal is seen as the root of many of our planet’s ills, but it is vital that the miners who toiled and often died getting coal should not be brushed aside and forgotten, as is so often the fate of soldiers who return home from unpopular wars.

DP Lindegaard is Kevin’s mother.

She is a local historian in Bristol, UK and is the author of the book Killed in a Coalpit

Leave a Comment