A good book deserves to be read more than once. A good reference book will be taken from the book shelf on a regular basis. A good biography of Aaron Copland needs to shed new light on a very well documented life. Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music & Cultural Politics by Carol A. Hess fulfils all these essential criteria and more. In fact, I would go as far to say that this excellent volume sits right at the pinnacle of the highest echelons of Copland scholarship!

Now this book is dense, and when I say that I mean it in a positive way. There is hardly a paragraph or page that goes by without a new nugget of information or a different take on something I thought I knew. I have had the book for over 18 months and trying to write a blog review has been daunting in the extreme. There are so many highlights that at times it seemed like a hopeless task to try and capture them all. The book is 254 pages and at one point my copy was labelled with 165 mini Post-it Note markers! I can only imagine the amount of time that Hess put into all this, reading countless references, translating them from Spanish and Portuguese and then bringing it all together into a succint, well argued treatise. It is a truly admirable feat.

Hess goes in depth into the historical context and Copland’s four Government sponsored visits to South American countries between 1941 and 1963 and his encounters with 66 composers and their music. She also delves deeply into Copland the man and perhaps more than any book I’ve read, explores and debates Copland’s own doubts, moments of melancholy, changes in opinion and frequent inclination to conclude arguments by sitting on the fence!

One of the best things about this book is it serves almost like a biobibliography with so many choice quotes by Copland, by others about Copland the man, on Copland’s music and plenty more besides.

It’s all fascinating stuff. I hope what follows below does this book justice and hopefully persuades you to buy a copy. In what is probably the longest blog of my career, I’ve tried my best to summarise the main themes.

What Copland thought of South American Composers

Anyone who has read any of Copland’s many books will know that he has a wonderful turn of phrase when describing the music of other composers. This is most pithy when he is describing their weaknesses.

Here are some of the best:

On the Argentine Carlos Suffern who played a piece for Copland during the 1941 tour “with much explanation”. Copland wrote:

some people talk a good game of tennis, Suffern talks a good composition.

Copland described Juan Carlos Paz’s compositions as looking well on paper:

As cool and detached and precise as any diagram. His scores are always a pleasure to look at but not always a pleasure to hear.

He also described him as a genius manque. I had to look this up. It means someone who has not had the opportunity to do a particular job, despite having the ability to do it.

In a similar vein Copland’s thoughts on Carlos Isamitt of Chile were that he composed in a

…highly fussy harmonic background, like a child pleased at the complicated shapes it is able to draw.

Copland lumped all Brazilian twelve toners into one category “dullards”.

Several of the composers whose work Copland dissected were quick to offer their reciprocal (and often barbed) thoughts on Copland (see section below).

There were many Latin American composers that Copland befriended. These were composers that typically shared a similar musical outlook to him. Carlos Chavez was a standout kindred spirit and the two were friends for 50 years. Others included:

- José Maria Castro (Atgentina) “at last a composer with fresh style and personality added to an excellent technique” and “refreshingly simple and direct”

- Mozart Camargo Guarnieri (Brazil) “Guarnieri is a real composer”

- Alberto Ginastera “the white hope of Argentine music”

- Juan Orrego Salas (Chile) “Juan was born to compose”

Copland had great respect for this group and dedicated three of the 12 Poems of Emily Dickinson to Latin composers: the Chilean Domingo Santa Cruz (Dear March Come In), Guarnieri (I felt a funeral in my brain) and Ginastera (I’ve heard an organ talk sometimes). In return eight tributes have been done by Latin composers for Copland. (Watch out for some blogs on Copland dedications and tributes as we approach Copland’s 125th birthday!).

Copland was cooler in his view of the music of two of Latin America’s biggest composer names. He visited the Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos eight times trying to pull off a coup to bring him to the US. On one occasion Villa-Lobos played Copland piece after piece from 4pm ‘til midnight. Copland wrote that

The Villa-Lobos music has one outstanding quality – it’s abundance. This is its primary virtue.

Hess also notes that Copland was put off by his “coquetry and ego of considerable size” and mentions that on another occasion his music making was akin to “getting away with murder”. (Shades of Walter Damrosch on Copland’s own Organ Symphony there.)

Copland met Astor Piazzola in 1947 and Hess says they “hit it off especially well” although the associated diary entry by Copland reports that he “didn’t get much of an impression” from looking at Piazzola’s Piano Sonata. In 1948 Piazzola went in for a competition to study with Copland and Darius Milhaud at Tanglewood (he entered Rapsodia porteña for Orchestra) but failed to win one of the three places available. Hess cites that Piazzolla was “crushed”.

Asterisked pieces and the chosen ones

Prior to this book I knew a lot of the works of Piazzola and a few pieces by Ginastera, Villa-Lobos, Chavez, Silvestre Revueltas and Arturo Márquez. This book provides a massive service by offering waymarks to a great deal of music to which I might have otherwise remained oblivious. Hess describes Copland’s Latin American encounters as “an ideal means of engagement” (for people like me to follow!).

Whenever Copland encountered works that he thought were of a high standard he would denote them in his diary with an asterisk. The best ones got three asterisks. Here are a few I noted:

- Jose Maria Castro – Sonata de Primavera ***

- Acario Cotapos from Chile – Three Preludes*

- Guillermo Uribe Holguin, a Columbia composer who Copland described as “a force to be reckoned with” – Suite Tipica*

- Jose Ardevol – Concerto for 3 pianos and orchestra, two concerti grossi, instrumental suite, sonata a 3 for two flutes and viola –Copland gae asterisks to two of these works (Hess doesn’t mention which ones).

After several of the state sponsored trips Copland made recommendations of the composers that should come to the US for exchange visits. In 1941 he recommended Guarnieri, Jose Maria Castro, Ginastera, Radames Gnattali, Carlos Isamitt and Uribe Holguin. Of the student composers he met, the ones that he thought most highly of were Héctor Tosar, Orrego-Salas, José Viera Brandäo, Cláudio Santoro, René Amengual, José Pablo Moncayo, Sergio de Castro and Salvador Moreno.

What the South Americans made of Copland and his music

Now frequent readers of my blog will know just how highly I rate Aaron Copland: The Life and Works of an Uncommon Man by Howard Pollack. However, if the 16 page section South of the Border from that book was your only source of information on Copland in Latin America, you would probably think that the love, affection and respect for Copland was an unbridled 100%. Certainly, it is the case that Copland was in most cases esteemed or even adored. Hess mentions that at one event that Copland was ushered away by embassy staff from insistent autograph hunters for his own safety. In other situations Copland could be mortified by the enthusiasm of his hosts, for instance Pablo Garrido’s idiotic, over the top effusions on a visit to Chile in 1962.

However, there were certain factions that preferred to level criticism at Copland with both barrels. There seems to be two schools of thoughts on Copland. Hess sums this up nicely. Copland was either a “market driven pompier purveyor of Technicolor music” or “a representative of fresh-faced US dynamism”.

(If like me, you don’t know what a pompier is it’s “an artist regarded as painting in an academic, imitative, and vulgarly neoclassical style”).

Here are a selection of some of the most notable positive and negative quotes about Copland cited in the book.

Brazilian journalist Nogueira Franca said that Copland defied musical “totalitarianism”

Copland was a rebel. Disinclined to dwell in an ivory tower, the composer pleases his public by drawing on the daily experience of life to produce music for posterity.

The Uruguayan Francisco Curt Lange remarked on Copland’s “dynamic temperament” and his “manifest inclination to Latin America and as a result…his friends and supporters, like a great part of the Latin American world, receive him as an old acquaintance.”

Chilean composer León Schidlowsky said “Copland was a cultivated man. Open to all truths , honest and modest which impressed me.”

Juan Carlos Paz admired Copland’s modernist works describing him as a “consumate master” and raves about the Piano Variations “strong aggressive, magnificently dissonant” and the Piano Sonata “full of tragic force”. However, it appears that he felt that Copland had betrayed his abilities in favour of “aesthethic nomadism” and “the laws of supply and demand” and in going all populist with his ballets, that Copland had become a victim of his own “aesthetic of opportunism”.

Carlos Suffern provides what is perhaps the most disrespectful scoff about Copland’s musical split personality infering that the artist “doth protest too much”:

After the concert, Mr. Copland, a man of simple habits, goes back home, reads a few lines from various music magazines, an article from the Reader’s Digest to stay up to date, writes down his impressions, drinks his glass of milk, and then goes to bed and sleeps like an angel….If only he could at least compose what he feels, if he could repeat without blushing the songs, the beautiful melodies, the persistent harmonies, the thick timbres, that he hears and loves! But he can’t. He’s a radical musician. What a dilemma! To be.

Hess brilliantly sums up this description by likening Copland to “a clean-cut Hamlet” sipping milk in an attempt to deal with his existential doubts.

In terms of Copland’s individual works and performances of these I was really intrigued that some of best reviews his music received in South America are compositions that don’t get much of a look in on concert programmes in the US or Europe. For instance:

An Outdoor Overture was described by various critics as “sublime” “freshest”, “perfect equilibrium”, “not a single false step” and “a school exercise composed by a master”.

Statements for Orchestra is variously described as “six little musical jewels…..(that) have few rivals in contemporary music” and “six brief movements of uncommon attractiveness”.

At one cocktail party in Bogata, Columbia, Copland’s Piano Quartet was played by the host as background music to “cocktail pleasantries”. I rather doubt it got the party in full swing! It immediately put me in mind of Leonard Bernstein playing Copland’s Piano Variations as a way of ending parties!

Not all of Copland’s works were universally well received.

In one concert in Rio in 1941 Copland’s As it Fell upon a Day and Piano Sonata were performed in what Copland described as “a very dense programme” also featuring songs by Ives, and chamber works by Virgil Thomson (Stabat Mater), Walter Piston (Violin Sonata) and Roy Harris (Piano Quintet). It’s the sort of concert I dream of but one critic (known only as JIC) said:

The heart is a dead muscle, one never heeded. It’s only the brain that works and produces, out of eagerness to grow something new and different within the formidable imaginary that is characteristically and essentially American.

Copland’s Piano Sonata was picked out as being indicative of the whole programme being labelled as “a work of solid structure, but absolutely lacking in any emotive sense”.

Lincoln Portrait had a definite Marmite effect (you either love it or hate it). Most critics hated it with one saying that it “doesn’t escape from being, at bottom, art with a message”. Another described it as a “movie dubbed in Spanish” and “we now know that the great Lincoln was 1 m 90 cm tall!”. Author and critic Jorge D’Urbano who applauded Appalachian Spring gave LP a big thumbs down saying “This mug shot of Lincoln has never struck me as gratifying” and “at least in Spanish, the effect is quite dreadful”.

Paz remarked on El Salon Mexico and Danzon Cubano that they were little more than “travel agency brochures” and the “nadir of Copland’s total oeuvre”.

Suffern damns Appalachian Spring with feint praise describing it as “a silent documentary in very nice Technicolor” whereas Adolfo Salazar writing on Copland’s ballets remarks that they “serve the client who has come to solicit (music) in Copland’s factory”.

Suffern sees Symphony No 3 as a pastiche of Russian composers – Prokofiev, Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rimsky Korsakov as well as Bartok, Schoenberg, Mahler and Puccini. He says

Pity that Tchaikovsky is romantic. Because (Copland) likes him and can’t come out and say so.

A critic who called themselves Oberon describes this work as “filled with the racket of machines” being the culmination of a “mechanical concert” from “the land of Uncle Sam”. He criticises Copland who he feels does not not allow himself to fully follow his natural inclination to romantic music and instead is “putting one over the public”.

Copland the cultural ambassador

Hess describes Copland as having “personal qualities fundamental to success as a citizen diplomat – “receptivity to other cultures, tact and curiosity of the world” and being “naturally gifted in person to person interactions”. His brand of cultural diplomacy was very much in the form of friendly persuasion to reach “a desired goal without arm twisting”. Hess asserts that Copland “deeply believed that peaceful relations in the arts could serve as a model for world peace”. With the rise of Nazism and later the Cold War, Copland was fully invested in the good neighbour policy and pursuing a “diplomacy of truth”. Hess points out that throughout his South American visits Copland followed the mantra put forward by Ralph Waldo Emerson

the only way to have a friend is to be a friend.

In certain circumstances Copland comes across as being very game. As an excellent linguist he was able to do lectures and present radio programmes in Spanish being a DJ on eight occasions during his visit to Rio. As always, he seemed to fully embrace the opportunity of the new.

It wasn’t all fun though. Copland’s diary entries indicate what he was prepared to do for his art and the different people he had to glad hand.

On the opening page there is reference to US Uruguayan ambassador and host O. Ellis Briggs that Copland described as “A better Groucho Marx”! One immediately imagines poor Copland cast as Mrs Teasdale and the styfling wooing by Rufus T. Firefly in Duck Soup.

In another diary entry Copland describes a diplomatic party “as one might expect…. DULL”.

One must remember that Copland’s forays across the continent were reliant on snail mail, telegrams and unreliable transport networks. In one situation he travelled 300 miles from Bogata to Cali in Columbia to find the conservatory closed and no one there to meet him.

Latterly Copland’s South American trips and links with the US State Department were picked over by his McCarthy led inquisitors during the 1950s Red Scare. I had always considered that Copland was relatively unscathed by his House of UnAmerican Activities experience. However, Hess reports that Copland’s works were subsequently removed from 196 US libraries worldwide. She describes this as an “gross injustice” not only “diminishing him personally” but also “a frontal assault on US music and cultural diplomacy”.

Unveiling Copland’s enigmatic shroud

Copland was known to be incredibly discreet and almost unknowable. In asking “Who was Copland” Hess provides some really insightful diary entries that show Copland’s inner thoughts in moments of fragility, solitude and loneliness.

In one passage detailing a visit to a monastery Copland suggests that the monastic life “seemed appealing, particularly if one removed the religious claptrap” but on his 1963 trip Copland seems depressed describing “a monk’s life” and slogging out lectures “it’s endless” in a Buenos Aires hotel room above a bustling street below. In another unusually candid entry Copland says:

its been a long time since I have been so little needed.

It’s so easy to think of Copland as being a confident raconteur who was secure in his own skin and able to handle every situation with aplomb but there are other entries that suggest vulnerability. On the 1947 tour he found himself in a situation with nothing prepared in Spanish and was reduced to reading from his book and gave a “terrible lecture” and “should never have agreed to do it”. Also in Argentina on the 1963 tour he had an evening meal with people that “all know eachother for too long and too well”. Hess infers from this, that despite appearances Copland was a loner at heart.

Hess is not afraid to throw light on Copland’s habit of waxing and waning between one view and another and his “many sided and conflicted” arguments offering opposing points of view on the same subject, sometimes within weeks of eachother.

In a review of Copland’s Our New Music, critic Theodor Chanler wrote that despite his “keen sensibility” and receptivity to many styles, he was “too modest to claim the last word when a point of doubt” arises. Instead, he says that Copland took refuge in “half diffident charitableness” revealing “softness of critical fibre”. Ouch!

Similarly, Hess evaluates Copland’s Music and Imagination and comes to a similar conclusion that “he vacillates” and “raised questions while ultimately hedging his bets”.

Hess contemplates this further in the introduction and conclusion with a slightly different lens each time. She accepts that Copland’s stance may be viewed as either “aesthethic waffling or innate flexibility” and “we may find his rhetorical half measures irritating or evidence of inner fragility”.

The last chapter Latin American Classical Music and Memory, covers an intriguing episode and Copland’s recollections of it. In 1957, Lincoln Portrait was played as part of a festival in Venezuela and it appears that over time Copland became convinced that the audience reaction to the emotive words inspired the first public demonstration against General Marcos Perez Jiminez and ultimately led to the revolution the folowing year. Hess lays out all the evidence and proves that “Copland’s story is pure invention”. This section could easily be a standalone essay on how the brain works and how people can embellish their own truth (or perhaps, believe their own BS). It talks about the “sin of suggestibility” i.e. “being convinced on something that never really happened, incorporating misleading information from external sources”. I was particularly interested in this as Copland has form – check out the passage in this blog about Copland’s slight amnesia regarding the use of a discarded Piano Variation in The Heiress film score. I guess in both cases the anecdote was good enough to repeat often and the more times he said it, the more the myth became reality.

Copland the eclectic

One of the things that really struck me was just what a big debate eclecticism was amongst composers. Now, I always have considered Copland’s ability to turn his talents to any particular style as an absolute attribute and one of the things that makes him truly compelling.

However, time and again “weathercock eclecticism” is levelled at Copland in a critical fashion and comes up about ten times throughout the book. Juan Carlos Paz, for instance describes eclecticism as “the antithesis of modernism” and Virgil Thomson is cited as saying that “Aaron Copland’s music is American in rhythm, Jewish in melody and eclectic in all the rest”.

I must admit it had me asking who of the great composers of the 20th century that I like weren’t eclectic? Certainly not Bernstein or Walton Or Stravinsky, Prokofiev or Shostakovich. It was obviously a big thing back then but nowadays I think it is an outdated argument considering that most composers have to be innately flexible and receptive to the market or choose not to work. Like so many things Copland was ahead of his time on that as well.

If only…. My wish list

I have a few points that are hardly criticisms but perhaps would make this book an even better experience for the reader.

As mentioned previously, this book is crammed with information. As a result when read in short bursts it’s sometimes hard to remember the where, when and who of it all.

It cries out for a timeline showing years and dates of Copland’s trips south and to which countries. Similarly, the myriad of characters is immense and some have similar names (for instance three separate composers called Castro) that it would have been so helpful to have a list of all 66 composers that Copland met providing their nationalities, dates of birth and death and the years when he encountered them. In moments of confusion, I was reminded of the time I read Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez. Hardly a night went by, sat in bed when I didn’t have to stop and think about who out of the two main characters (Florentino Ariza and Fermina Daza) was the male character and who was the female!

Furthermore, a list of all of the compositions that Copland gave asterisks too would have been a real asset. I will have to go back through the book to do this as I have only captured a few above.

Finally, I would have loved for there to be a short discography of some of the works mentioned. I was really disappointed to find how badly served South American composers are on Spotify. It made me ask Google the question “Is the Spotify content available in Europe the same as it is in South American countries?” It appears not – Spotify’s library varies by country due to licensing and copyright restrictions. This means that some songs and classical music works might be available in Europe but not in South America, and vice versa. This is a great shame as it means that so many of the gems mentioned in the book are not easy to acquire. YouTube has a wider selection but hardly any of the works Copland approved of during his visits seem to feature anywhere. Isn’t it ironic that more than 60 years after Copland’s last tour, that this incredibly rich musical heritage remains a bit of a closed book to most North Americans and Europeans?

Perspectives on Latin America

I think a cultural ambassador like Copland would be an asset in any age, but perhaps now more than ever before. Hess sums it up nicely at the end of introductory chapter as follows:

Despite some missteps, Copland’s efforts in Latin America are a tribute both to his psychological resilience and his commitment to world peace. They also serve as an example for the present, when the role of the U.S. State Department – and indeed, the place of the United States in the World – spark heated and often partisan debate.

For my part, (despite one visit to Ecuador and the Galápagos Islands back in 2001) South America remains truly exotic and remote. I guess that it might be due to the fact that because of British colonialism and the Empire once stretching to Australasia, the sub-continent of Asia, South Africa and North America that I have been brought up on a shared history largely spoken in English. Nevertheless, I have always been intrigued by the South American continent, the natural history, the music and the people but like Copland it seems enigmatic. Perhaps I am guilty of the same charge levelled in the introduction of the book

People of the United States would do anything for Latin America except read about it.

I believe that for anyone interested in music, immersing yourself in this wonderful book is a perfect way to begin to redress that balance.

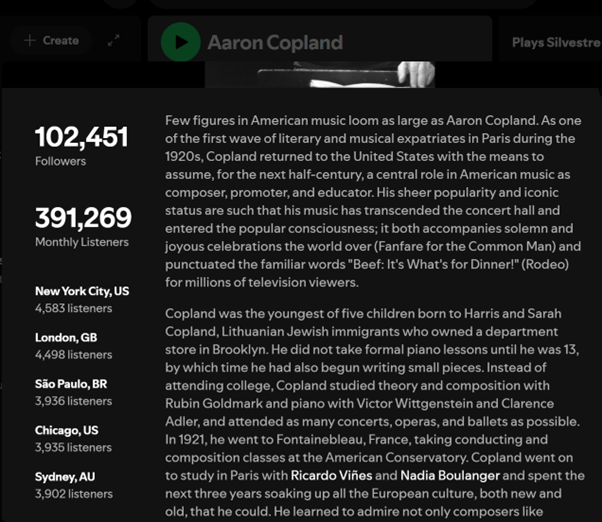

An afterthought – Aaron Copland in Latin America today

Whilst looking for Latin American composers on Spotify I noticed an intriguing fact. Copland currently has 391,000 monthly listeners. After New York and London, Sao Paulo in Brazil seems to have the third highest number of Copland listens per month! So, it appears that even today, Copland’s music is still providing a cross border cultural handshake!

Book details:

- Name: Aaron Copland in Latin America: Music and Cultural Politics (Music in American Life)

- Softcover: 344 pages

- Publisher: University of Illinois Press (28 Feb 2023)

- Language: English

- IISBN-10: 0252086953

- ISBN-13: 978-0252086953

Leave a Comment